The Trend That is Becoming a Movement

Why so are so many young Evangelicals moving towards more liturgical traditions? And what does that tell us about our churches?

I wasn't planning on writing this article today, but while sitting in a local coffee shop this morning, I overheard two separate conversations that provided the activation energy necessary for this endeavor. The first was between an older man and a middle-aged woman discussing their faith and life at their evangelical non-denominational church. From what I could gather, the woman was employed by the church in some kind of preaching/teaching role. They were discussing a strange new movement they had observed among young people in their congregation—and even in a few of their own family members.

The second conversation was between two young men discussing their evangelical upbringing, their drift from faith during college, and their recent embrace of Roman Catholicism.

As someone who grew up in an Arminian, egalitarian, nondenominational church—who now holds Reformed Baptist convictions and serves a Calvinistic, complementarian, nondenominational church—eavesdropping on these conversations was both fascinating and unsettling. They provide anecdotal evidence of a trend that many keen observers have noted, one that I suspect will become a significant movement that will perplex many evangelical Christians.

Just yesterday, I had coffee with a young college student who grew up as a non-denominational evangelical. He told me about how he was becoming increasingly interested in considering the validity of pedobaptism, baptismal regeneration, and transubstantiation. When we finished praying together at the end of our meeting, he made the sign of the cross.

We need to talk about why so many young Christians are abandoning their evangelicalism in favor of Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and other more formal traditions.

In this article, I will consider this issue:

First, by providing evidence for this trend that is becoming a movement.

Second, by examining the key factors that are driving this movement and how this underlying impulse manifests itself in evangelical churches.

Finally, by asking the question "What does this tell us about our evangelical churches?” and defining potential solutions.

I am a convinced Reformed evangelical. I believe that Reformed evangelicalism is the purest expression of biblical Christianity and can thus provide good, biblically sound, historically rooted, satisfying answers to the trends we are observing.

Evidence of This Movement

While empirical data on Gen Z's migration away from evangelicalism and towards more liturgical traditions remains sparse, the empirical data is slowly catching up with the anecdotal experience of many in the nondenominational world. Just a few months ago, the NY Post ran this article…

Young men leaving traditional churches for 'masculine' Orthodox Churches

While I find their analysis… limited, I think the mere fact that the NY Post is noticing trends of migrations within Christendom is noteworthy. In this article, they note that since 2019, Orthodox churches in the U.S. have experienced a 78% increase in converts with a significant rise in male membership.

Now, we must keep in mind that at a broader level, Gen Z is generally less affiliated with traditional religious institutions compared to previous generations. Approximately 34% of Gen Z identify as religiously unaffiliated, a higher percentage than among Millennials (29%) and Gen X (25%), according to the American Survey Center. Whether these statistics are predictive of how Gen Z will behave in the coming decades is a conversation for another time (I would suggest they are not). The point is that this 78% increase in converts among Eastern Orthodoxy is not the result of revival happening in the Eastern Orthodox church. These aren't unbelievers who are becoming Orthodox. These are former evangelicals who are deconstructing from the Christianity of their childhood and reconstructing it into something very different.

This trend isn't limited to Eastern Orthodoxy. According to Catholic365:

"Observations indicate a resurgence of interest among young adults, particularly those aged 18 to 45, in traditional Catholic practices. Many are drawn to the church's rich traditions and are actively participating in Masses."

Figures like Bishop Robert Barron have effectively utilized digital platforms to engage younger audiences. His Word on Fire (a Catholic Ministry) presents Catholicism in a profound and intellectually stimulating manner, appealing especially to young men seeking depth in their faith.

The same trend seems to be true among the Anglican communion. Despite the incredible turmoil that has been present among the Anglican church in recent years1, The Anglican Church in North America (ACNA) has reported growth, with Sunday attendance reaching an all-time high in 2023. This increase suggests a renewed interest in Anglican worship, which is known for its liturgical richness.

Suffice it to say, anecdotal evidence for this trend that is becoming a movement is plentiful, and the empirical evidence is catching up.

Why Is This Happening?

I imagine this trend is surprising to most. After all, it is the exact opposite of what we have been observing within Christendom for the last 50 years, where Catholic and Mainline churches have been bleeding members while evangelical churches have held fairly steady. It begs the question: what is driving this movement?2

(credit, Ryan Burge)

That's a complicated question, and complicated questions deserve nuanced answers.

I want to suggest three key factors driving this trend-turned-movement. While this won't be an exhaustive treatment of the issue, I hope to provide a thorough and thought-provoking analysis.

1. Young People Have a Craving to Be Grounded in Tradition and History

In 1962, Austrian-American economist Fritz Machlup coined the phrase "half-life of knowledge"—a term describing the time it takes in any given field to discover that half of what you thought you knew is actually mistaken. In other words, it measures how quickly ideas around a particular subject are changing.

I would argue that as a society, our philosophical half-life of knowledge has never been shorter. Our world has changed—and is changing—faster than ever before. Ideas, world views, and popular moral convictions have shifted at such a rapid clip that it feels impossible to even keep track of it all.

I think the most illustrious example of this has to do with how cultural attitudes have shifted towards so-called "gay marriage" in the past 25 years. Ask yourself the question… "Who is the first American President to run for office on an openly pro-gay marriage campaign?" Obama? Clinton perhaps? No… it was Donald Trump in 2016.

In 2012, even the liberal candidates would not openly embrace so-called "gay marriage". Now, our social imaginary has shifted so dramatically that it seems unthinkable that even the most staunch conservative would oppose it.

I use that example to highlight how our society is changing at a breakneck pace, both morally and philosophically, and I argue that this has had a significant impact on the minds of many young people. In a world where everything feels unstable, insecure, and always shifting, young minds crave something that they can trust—something that has stood the test of time, something larger than themselves, and can help them escape the moral, philosophical, and intellectual disaster that is our postmodern world.

Unfortunately, many of our evangelical churches (especially non-denominational ones) have failed to provide this historical grounding, even though it's precisely what Historic Christianity has to offer.

If you had a time machine, and visited your chosen non-denominational church in 2000, 2010, 2020, and 2025, it would probably feel like four radically different churches. Evangelicalism generally has not done a good job of maintaining the timeless traditions of the faith. Instead, due to our intrinsic consumerism and populism, we have been quick to adopt the latest cultural fads. We have been a Church easily swayed by the larger cultural ethos. We will return to this conversation when we consider some potential solutions to this problem, but my point here is that young people have a desire to be part of something rooted in history and tradition. Many evangelical churches have not done a good job offering that, and in response many Gen Zers have decided to look elsewhere.

Say what you will about the Catholic, Orthodox, or Anglican churches, but they at least claim historical continuity. They don't appear to be changing with the times and seasons (though they really have), and that appearance of historical continuity is attractive to a lot of young people.

2. Young People Crave a More Well-Developed “Post Conversion Theology”

“Ok… what now?”

I didn't say that out loud when I professed faith in Christ at 10 years old—I didn't even know it was a question I had. But it was, and it largely went unanswered growing up as a non-denominational evangelical. I had been taught, and genuinely believed, that I had sinned against the God who created me (Rom 3:23). But God so loved the world that he sent his only Son (Jn 3:16). Jesus Christ, who is the Son of God, died on the cross, paying for my sins, and by trusting in him, I could enjoy eternal life (Rom 6:23). I was assured that once I had made this profession of faith, no matter what I did for the rest of my life, I could never lose my salvation (Phil 1:6...sorta).

This was the gospel that I received and believed from a young age, as did many evangelicals my age. The problem is, I was only 10 years old—what was I supposed to do for the next 70 years of my life? Am I just killing time, waiting to die and go to heaven? I have BEEN SAVED (past tense), so what else is there for Christ to do for me? Why should I go to church? Why should I read my Bible? Why should I pray? Again, I didn't voice any of these questions, but they were there subconsciously and hamstrung my young faith for years.

Generally speaking, this kind of conversionistic theology has been a hallmark of American Evangelicalism ever since the Second Great Awakening. We have in many ways conflated justification with salvation, and in doing so, we have severely truncated the gospel. I would argue this shallow theology leaves Christians feeling stagnant, stunted, and unmotivated—and in the case of many young people, looking for alternatives.

Interestingly, I think this basic desire for a more robust post-conversion theology has manifested itself among young evangelicals in another way.

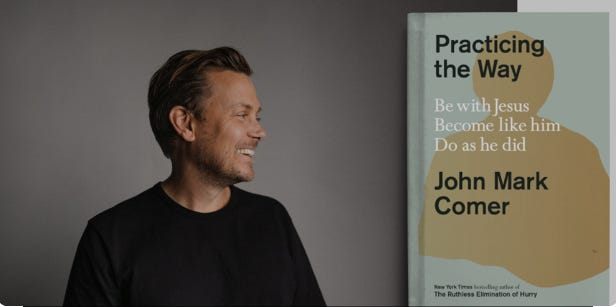

John Mark Comer is undoubtedly the most popular, influential voice among young thoughtful evangelicals today. His books "Live No Lies," "Garden City," and "The Ruthless Elimination of Hurry" have catapulted him into pop-Christian superstardom. In 2024, his most popular book "Practicing the Way" became a New York Times bestseller. As has been said, “This is comers world, and we are just living in it.” Now, I think Comer is best taken with a hefty dose of skepticism (an article for another time) but there is no denying that he has put his finger on a deep-felt need.

What can explain Comers’ explosive popularity among young evangelicals? I would suggest that Comer offers a more developed post-conversion theology than most of the evangelical world has in the past 20 years.

The core thesis of "Practicing the Way" is that Christianity is more than just a set of doctrines to believe—it's a lifestyle to be lived out. It's a following after Jesus, being his "apprentice." Literally, it is a way to be practiced.

Is Comer's "Post-Conversion Theology" biblical? Well... sometimes. But is it more well-developed than what most of evangelicalism has offered lately, and consequently powerfully attractive to young Christians? Absolutely

3. Young People are Open to Mysticism in a way that Previous Generations Were Not

Finally, I would suggest that young people are open to mysticism3 in a way their parents' generation was not. The reasons for this newfound openness to mystical and spiritual experiences are numerous, but let me offer a few key insights.

First, in recent years young people have become dissatisfied with the materialistic naturalism that was deeply embedded in previous generations' worldviews. In his 2007 book, A Secular Age, Charles Taylor highlights how even among those who profess to believe in God, many live as if only the tangible and empirical matter in daily life. He describes the modern understanding of self as a "buffered self"—where a person is closed off from the spiritual world, even while professing belief in it. As a result, people who embrace this worldview become practical materialists, though they may not themselves claim philosophical materialism.

To many young minds, this philosophical and practical materialism rings hollow. The rationalistic worldview espoused by atheism has failed to provide a satisfying explanation for our existence, leading young people away from purely rationalistic thinking. This shift is evident in their widespread embrace of new-age spirituality.

These changes in thinking are not surprising. After all, the desire to move beyond a strictly rationalistic worldview drove the shift from modernism to postmodernism. However, while pluralism is the alternative to rationalism in the postmodern mind, I would argue that mysticism is the alternative to rationalism in the minds of many young people. In this sense, they are not so much postmodern as post-Enlightenment in their thinking.

This new, almost post-Enlightenment way of thinking makes more mystical traditions, such as Eastern Orthodoxy, plausible in the minds of young people. As post-modern thought has wreaked havoc on the faith in the West over the past 25 years, the evangelical church has clung to modernism to fend off the postmodern zeitgeist. Young people don't like post-modernism, but they're equally turned off by modernism, and their solution has been an embrace of mysticism.

What Does This Say About Our Evangelical Churches? What are some Potential Solutions?

Watching this trend become a movement should catalyze us as evangelicals to engage in serious self-reflection. What does this movement reveal about the current state of evangelicalism, and how can we address it?

We must embrace the historical roots of our theology

First, this trend reveals that we as evangelicals have failed to demonstrate our faith's historical credibility. For the past 25 years, evangelicalism—particularly in non-denominational churches—has increasingly distanced itself from the past, implying that historic Christianity somehow got the faith wrong. This mindset suggests that Christians of former centuries were dull and unenlightened, while we modern progressives have rediscovered the true heartbeat of the faith and somehow cornered the market on pure Christianity. Many evangelical church leaders today have enthusiastically embraced a kind of biblicism that says “We have no creed but Christ, no book but the Bible, no law but love.” In other words… we are confident that we understand the bible all on our own, and we have little need for history or tradition.

That kind of thinking has to stop. For starters, it has been proven to be untrue, evidenced by the highly transient nature of non-denominational evangelical churches today. If we have such a clear understanding of Christianity… why does it seem like we are so rapidly evolving?

Beyond that, this anti-creedal, anti-historical attitude contradicts historic evangelicalism. We as modern evangelicals need to return to the Reformation doctrine of Sola Scriptura, which holds Scripture as our final, supreme authority while embracing creeds, confessions, and church history as valuable guides that help us understand Scripture correctly.

If we as evangelicals claim to be ministers of “the faith once for all delivered to the saints,” we must show how our Christianity has deep historical roots—traceable through the Puritans, the Reformers, the Middle Ages, Augustine, the early church fathers, and ultimately back to the apostles themselves.

We must articulate a more robust theology of salvation

Second, as evangelicals must articulate a robust post-conversion theology to our people. The "walk the aisle → pray the prayer → once saved always saved" theology that so many evangelical churches have embraced is

A) Not Biblical

B) Not Satisfying

Salvation involves more than justification. It means being united to Christ in his death and resurrection, enjoying fellowship with him as we are transformed progressively into his image. Salvation is a past, present, and future reality for the Christian. As Jonathan Edwards said, "Seeking God is the central pursuit of the Christian life." Conversion is not the end of the journey for believers—it is the beginning. We as evangelicals must embrace and proclaim to our people the truths of Philippians 3 where the Apostle Paul says

I count everything as loss because of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord. For his sake I have suffered the loss of all things and count them as rubbish, in order that I may gain Christ 9 and be found in him, not having a righteousness of my own that comes from the law, but that which comes through faith in Christ, the righteousness from God that depends on faith— 10 that I may know him and the power of his resurrection, and may share his sufferings, becoming like him in his death, 11 that by any means possible I may attain the resurrection from the dead.

12 Not that I have already obtained this or am already perfect, but I press on to make it my own, because Christ Jesus has made me his own. 13 Brothers, I do not consider that I have made it my own. But one thing I do: forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead, 14 I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus. 15 Let those of us who are mature think this way

Php 3:8–15.

We must communicate a more biblical and intellectually satisfying theology

Lastly, we must present a well-developed, biblical, and systematic theology to our congregations. Young people are embracing mysticism largely because the theological systems they've encountered lack intellectual depth and satisfaction. This is unfortunate since the Bible contains a consistent, coherent, intellectually stimulating, and deeply satisfying theology that can be conveyed through sound exegetical preaching and discipleship. We don't need mysticism to fill gaps in our theology. As pastors, we simply need to present a more robust and biblical theology to our people.

Thank you for reading! While this is not an exhaustive treatment of this broad issue, I hope this article encourages deeper thinking and sparks meaningful conversations among fellow believers. I'd love to continue this discussion in the comments or feel free to reach out to me directly via DM. If you found this article thought-provoking, please consider sharing it with your friends!

This graph belongs to Ryan Burge. Check out his excellent substack for more of this kind of material

J.I. Packer describes Mysticism as "an approach to God that seeks direct, unmediated experience with Him, sometimes through contemplation or ascetic practices, but which can become detached from the objective truth of Scripture." Packer acknowledges that while some historical Christian mystics were orthodox, mysticism often leads to theological error. (See Concise Theology)

As a part-time seminarian myself, I think your three reasons are correct but incomplete because you underrate the substance of the traditional luturgies. It's not just that those luturgies are an anchor in turbulent cultural waters. They aren't historic and traditional for the sake of being historic and traditional - practitioners think there is something faithful and compelling and useful in those luturgies.

With this in mind, I submit that your three solutions, which boil down to theology, theology, and theology, are a bit like the "they don't know" meme. "They don't know how historical, deep, and satisfying our theology is!" Meanwhile everyone else is (or thinks they are) encountering God Himself every week through liturgical worship in ways they never did or could in reformed evangelical churches.

Very good! I especially agree with your three key factors — those definitely seem to be behind the shift. You put your finger on it.

I’m not exactly young (42), but I am part of this shift, and I’ve been increasingly drawn to the liturgical and sacramental practices of Anglicanism over the past couple of years. From my perspective, the idea of a more “intellectually satisfying” faith that you posit as a solution didn’t do the trick for me: If I wanted intellectual rigor, I’d simply dig deeper wells in Reformed theology. Instead, I got to the point that a primarily intellectual faith wasn’t enough, and I began to hunger for a more physical, experiential, embodied, and sacramental faith. To put it crudely, I found that it was no longer enough to order a Banner of Truth volume that would help me think truer thoughts about the Lord’s Supper, and instead simply found that I was hungry for the body and blood of Christ.